This is a project about China – the world’s second largest economy – and about capital markets, the foundations of the post-Bretton Woods global financial order. In 1989, capital markets did not exist in China. Fast forward three decades and China had become home to the world’s second largest stock, bond and futures markets globally. And whereas China’s markets have been virtually closed from the outside world for decades, especially since the global financial crisis 2007-2009 they have become connected to global markets ‘at an unprecedented pace’. While previously peripheral to its bank-based, state-controlled financial system, capital markets have gradually become an important pillar of China’s political economy. However, capital markets are often assumed to have liberalising effects. In IPE literature ‘global’ capital markets are usually discussed as forces that facilitate an increasing convergence of economic activities according to a (neo)liberal playbook, while in CPE research capital markets are viewed as the dominant coordination mechanisms of financial systems within liberal market economies. Capital markets are understood as one particular form of economic coordination, but they are often conceptualised as uniform entities and as primary facilitators of a convergence towards a liberal, Anglo-American model of capitalism. The growth and internationalisation of capital markets in China’s non-liberal economy therefore poses an important puzzle.

The central argument of this book project (under contract with Cornell University Press) is that capital markets are not uniform entities and that capital markets in China function fundamentally different from ‘global’ markets because the organisation of these markets is informed by different institutional logics. The book demonstrates that the defining difference between liberal and state-capitalist logic is not the existence and prominence of capital markets per se but rather the principles that underlie market organisation (profit creation vs state objectives) and the actors that dominate/shape these markets (private finance capital vs state institutions). While the primary underlying principle of global markets is to create ‘efficient’ outcomes by enabling profit creation for private finance capital (liberal logic), in China the primary underlying principle is state control of market behaviour and directing market outcomes towards national development objectives (state-capitalist logic). Consequently, Chinese capital markets function differently, fulfil different socio-economic roles and lead to different societal outcomes than global markets.

The projects’s analytical focus thereby lies on (Chinese) stock and futures exchanges. Rather than investors that are active within markets, exchanges play a much more architectural role as they create the infrastructural arrangements that enable the functioning of capital markets in the first place. From market data access, which financial products are traded to trading rules, exchanges shape the characteristics of capital markets. They are powerful actors that define the rules of the game according to which capital markets function, but their organisation of markets is heavily influenced by their institutional contexts. How exchanges are governed and which constraints and incentives they face matters: within Chinese state capitalism and Anglo-American liberal capitalism, exchanges create fundamentally different capital markets.

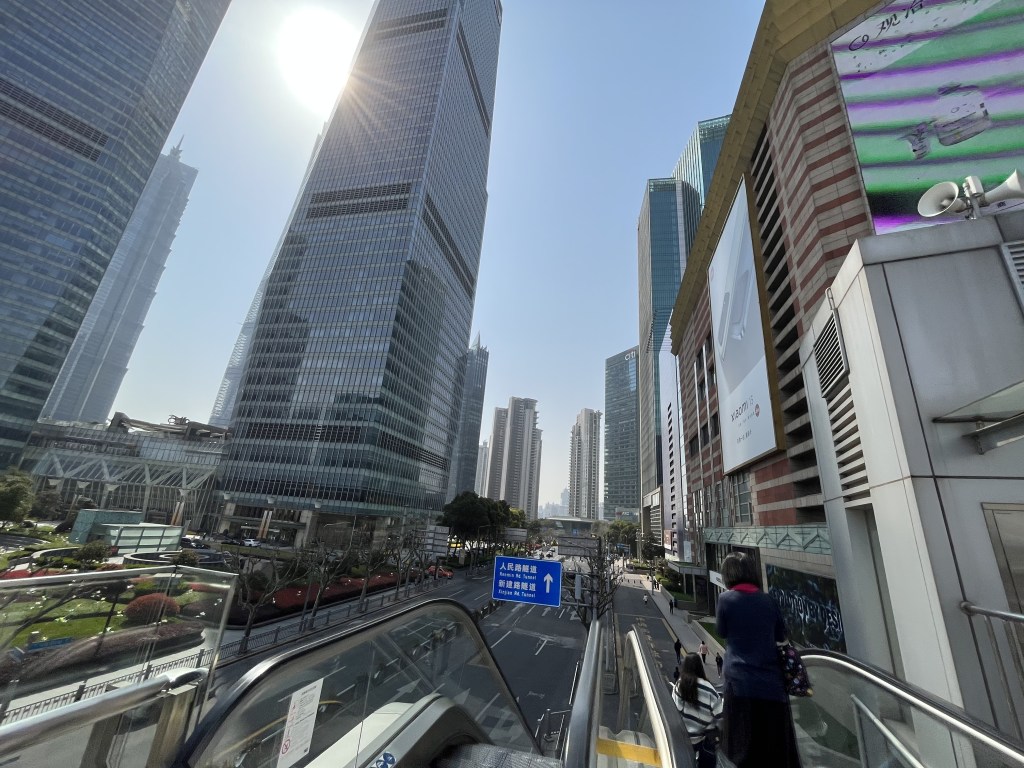

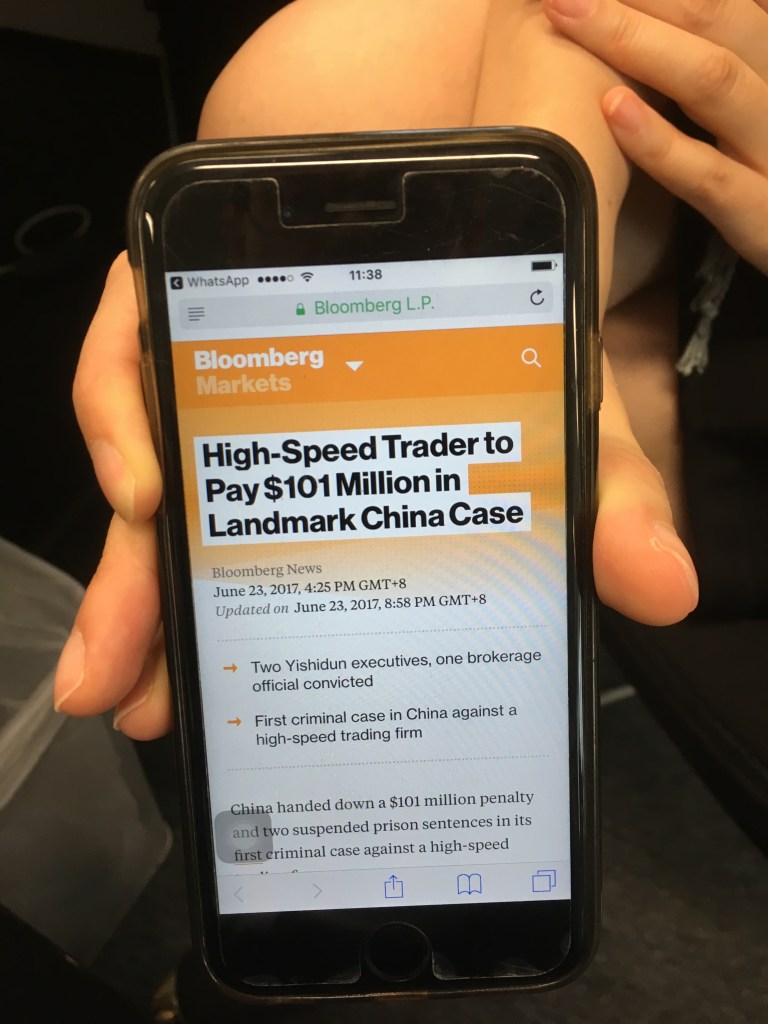

Drawing on a multi-method research design, this research is based on an analysis of descriptive financial statistics, policy documents (e.g. trading rulebooks, regulatory reports), financial news coverage as well as 200+ expert interviews and ethnographic data from 40+ financial industry events collected during nine months fieldwork in Shanghai, Beijing, Hong Kong, Singapore, London and other international financial centres between June 2017 and March 2023.

____________

major publications

Petry, J. (2025). China’s quest for pricing power: Financial hierarchy, autonomy and commodity futures markets. International Affairs, 101 (5), 1747–1768.

Petry, J. (2024). China’s rise, weaponised interdependence and the increasingly contested geographies of global finance. Finance and Space, 1(1), 49-57.

Weinhardt, C., & Petry, J. (2024). Contesting China’s developing country status: Geoeconomics and the public–private divide in global economic governance. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 17(1), 48-74.

Chen, M. & J. Petry (2023) What about the dragon in the room? Incorporating China into international political economy (IPE) teaching. Review of International Political Economy, 30(3): 801-822.

Petry, J. (2023) ‘Beyond ports, roads and railways: Chinese economic statecraft, the Belt and Road Initiative and the politics of financial infrastructures‘, European Journal of International Relations, 29(2): 319-351.

Petry, J. (2021) ‘Same same, but different: Varieties of capital markets, Chinese state capitalism & the global financial order’, Competition & Change, 25(5): 605-630.

Petry, J. (2020) ‘Financialization with Chinese characteristics: Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism’, Economy & Society, 49(2): 213-238.

____________

fieldwork insights